One of my literary heroes, Jack Saunders, helped me to look at art in a new light. His own work has often been considered to be a 0 on a scale of 1 to 10. Others call it a 10. So what’s going on? Everyone has heard that beauty is in the eye, that it’s a matter of opinion. But Plato never thought much of opinion, so maybe we shouldn’t either. We need to know!

Here’s an approach I recently saw mentioned online by an Ivy Leaguer: “My only question of art is if it’s interesting or not.” Hmmm, seems lacking. Trite. Static. Snotty.

Here’s another approach, which seems a bit better, which I found courtesy of Google: “Knowing the difference between good and bad art can be difficult. You can’t always trust the art experts; many times it’s hard to even understand them. Since I believe that it’s important to make up your own mind about art, I decided to write this article to help each and every one of you judge art for yourself. … I’ve come up with five characteristics that you can use to determine the quality of art … beauty, skill, inherent meaning, uniqueness, and fulfilled intent.” emptyeasel.com/2006/11/18/how-to-judge-art-five-qualities-you-can-critique/

To me, this is close but not quite there. Beauty? Skill? Too much waffle room. And answers there might have NO BEARING on you. I don’t care about art per se. The writer of the five characteristics essay says that art can have inherent qualities. But to me it never stands alone. It needs us to see it. Otherwise it’s just something a bird might perch on.

If you pretend that art stands on its own all sorts of cultural programming sneaks in. The “stand alone” facts are a cover for LIES. Art is instead about relation. It’s about you and me. And relations can be knowable, can be factual. A meaning is a fact. Let’s look at the facts that connect art to our lives!

I think judging art should be a path to YOU getting more out of life, to seeing life better. Judging, or, more importantly, using someone else’s judgement, needs to be direct and relevant to YOU. So, skill and those other five characteristics are all important, but only as they relate to you.

Whether art is entertaining or fun or not is also not the whole story. Those responses are often static — they relate to you as you are, they work in your comfort zone — even if they tweak it. These factors influence what’s superficially engaging. They’re important, but they aren’t reasons for art nor are they its content. Art that is only about such things is only about killing time, recharging, distracting or numbing us. It’s interesting to note that amusement comes from the Latin for “against the muses,” entertain relates to enchain and contain, and passion is largely passive. Be careful out there! : )

To me, despite feelings one has about art, one should focus on the facts of meaning. It’s not important whether it was hard to use such a tool in such a way to get such a result. “See the tiny detail!” …Who cares! I’m talking about *set and setting*. That’s the path to the important stuff!

So, try answering the following five questions whenever you see art. They’re pretty straightforward, needing no special knowledge or training. But since we regular folk can’t always know the set and setting of art, when you read/hear the critics who should know such things, check to make sure they’re answering them.

1. What is the artist attempting? What are the questions he poses, the challenges he gives himself? Trite or meaty? Does he set up straw men or go for the heart of the matter?

2. Does the artist achieve what he set out to do? No one is perfect, so to the extent he fails are his failures understandable, or to be held against him? The bigger, bolder and braver the attempt the more slack and tolerance we allow. Is he lazy? Does he blunder from willful blindness? This sort of failure is less tolerable. What is his situation? Is he working in the best of situations which unlimited support? Is he working out of a dumpster? We’re more impressed by the artist who makes do.

3. Have you seen similar attempts? Compare artists. Is another artist doing the same thing better? Is there room for both? The art might be about a subject that is rarely treated, making a “more the merrier” situation.

4. Is the artist pushing his heritage further or rehashing old stuff? What tradition is the art part of? Does he declare himself to be part of a tradition? Is he right? Is he up front about where he comes from? What is his situation like? Is he supporting the powers-that-be, currying their favor? That’s a tradition. It’s the tradition of the employed, the professional, one who is part of a program. How does his heritage relate to your own? We’re usually not all of one piece. Part of us relates to our job and the concessions we’ve made. Part of us yearns for freedom. When you react to art (or to a review), notice what part of you is reacting. It’s hardest to admit something that explores our worldview — and, in particular, our way of making money. Defensiveness is often masked as disgust or boredom. It helps to focus on ‘whose ox is being gored’ or even challenged when evaluating a response. How comfortable are we ever with the truth? Meaning, a truth about ourselves, at our current place in life.

5. Lastly, is he telling the truth? This isn’t as easy as it might seem. You have to push hard to get close enough to earn respect. Mistakes are part of the path. Suffering and tragedy arrive — but comedy can be part of it, too. Superficial truth results in simple facts, unexamined contradictions. Some artists coast along in a setting without even acknowledging they’re in it. Finding useful truth involves resolving or at least confronting one contradiction after another. Is the artist on such a path?

***

I’d say that questions like these can help point us to the best and most relevant art for us, here and now.

I think they also strongly relate to and help clarify such abused words as beauty and skill by helping us see the cultural aspects of them. If an artist is up front about their culture on levels that relate to US then I think that relates to a process where truth and even ugliness are elevated to beauty and where skill is revealed. I think questions like these also help us to sort out the relevant kinds of badness in art. How does the beauty relate to me? How does the skill relate? What does it MEAN? Not on its own — that can’t be — but TO ME NOW. But that’s so relative, you might say. Well, sure.

Art can be good for today. It can be ephemeral and still of great service. The test of its relative greatness is if it can KEEP relating, can KEEP being relevant to you, as you change. Good art isn’t blind — it sees; it isn’t attached — it’s free. To the extent that it sees and is free, it can keep meaning something newly relevant to you in all your next NOWs.

***

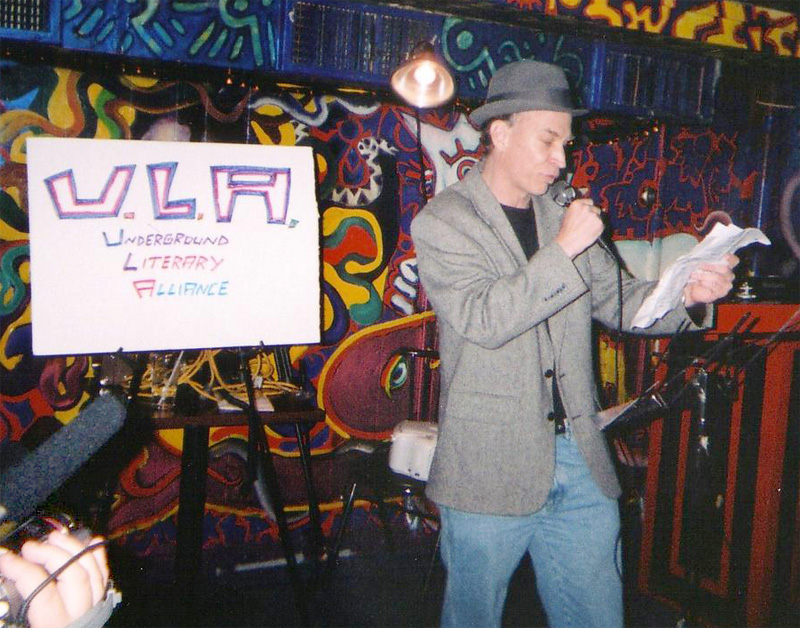

I think that the line of ULA novels relates strongly to the ideas presented above. They might be rough in some ways, but they rank higher in other — maybe more meaningful — ways.

By extension, folk writing in general deserves a far higher esteem in our culture. Yet it’s not even admitted as existing by many authorities. “Folk” is still often defined as being illiterate. No one is illiterate anymore. But there is still folk out there. Times change. But ideas about post-literacy haven’t yet caught up to most folk studies. Let’s push!