(…Kind of longwinded…)

Trapping is a tricky thing, due entirely (I think) to its growing unfamiliarity to so many. The “familiarity” a lot of people have with it comes from intentionally alienating media and websites depicting it out of context.

“Silent Sports” magazine ran a profile this winter of an old trapper who used to cruise his trapline on snowshoes to the tune of 30 miles a day. The farther north you go the more common such a life would be. I was happy to see such diversity in the magazine. The article did a good job of tying cultures together, showing common bonds.

Of course, the next issue had a standard, boilerplate anti-trapping letter.

As you might know, I really like stories where barriers are jumped, where things like silent sports and rural ways are shown merged together, as they often are in real life. Snowmobiles, ATV’s and guns aren’t always on the “other” side from bikes and XC skis. Any report that reveals “we’re all in this together” does good service, in my view.

Many silent sports people are also “hook’n’bullet” types, after all. I know that I am. (I XC-skied all winter. But I also used an ATV — for transport at a remote cabin. We even used it to tow a group of skiers to a trail system, like group water-skiing.)

Back to trapping… I haven’t done it for years, myself. I sympathize with the views against it. Obviously, any civilized person would be against trapping. It’s a slam-dunk “issue”, right? But I see more going on here in this classic, proto-typical confrontation.

First, in any two-sided debate either side can “win” depending on the skill of the debater. More sides than two are needed for real truth and true realism. Life experience, for instance. So this isn’t a defense. Just some ruminating. I’m not saying I have the answer, just some experiences, and thoughts.

Secondly, I see that the higher consciousness aspect is indeed involved here. As civilization advances we try to become more humane. Some good people used to see no harm in flogging, some treated their chattel well — meaning their wife and kids and other livestock — some treated their slaves well. We used to mow down the virgin forests of entire states and freely dump toxins. Now we don’t. We move upward past those things as we see the inhumanity in them.

It’s easy to put trapping into a low-down category.

We might accept that Native Americans and other heroes of the outdoors did trapping as recently as, say, the 1930’s, when Elliott Merrick wrote his classic tale of cityboy-meets-northwoods, “True North.” (On my desk right now.) But we’ve put such things behind us today, right?

…Except that the closer you get to nature, to living off the land, the more time stands still, and the more trapping comes into the picture.

Just know that if you’re against trapping, you’re against a lot of good people.

Instead of arguments, for questions about Life it might sometimes be appropriate to consider simple stories or reflections.

Did you know there’s a “Trapline Marathon” in Canada, hosted by the Trappers Running Club? They’re paying homage to their local heritage of living — even today! — off the land. www.traplinemarathon.ca

How about the Conovers? Alexandra and Garrett are northwoods guides and authors of classic outdoor skills books. They blend old and new ways for the tours they run into the bush. Educated by their Native American / First Nation neighbors, they combine snowshoes … and snowmobiles, guns … and tobaggans. They say it’s sometimes off-putting to their city clients, but that they soon come to understand. The Indians certainly trap. www.northwoodsways.com

Then there’s Trapper Norm. He was an old codger who lived in a cabin out at the far end of the famous Stokely Creek XC resort in Soo, Ontario. At the lodge it’s like any resort—a fairly narrow slice of uppercrust life — but if you skied way out you could have lunch with an “immoral” old trapper — and thousands did over the years. He trapped almost as long as he lived. He also was a no-ropes high-rise ironworker of the old type, along with the Mohawks. He recently died at age 94.

Stokely also once had a manager, Mike O’Connor (who’s still involved up there) who ran a dogsled team at the resort (activists would stop that, too). He was a trapper. He wore amazing furs. And archeologist. And ornithologist. He even groomed trails for snowmobiles, as well!

What about Solomon Carriere, the great marathon canoe racer from Saskatchewan? His family and relatives are still semi-nomadic, living in the bush, running traplines.

The truism is that the farther off the beaten path we wander the more likely we are to run into people who live (partly) off the land by a diverse range of sustainable hunting, trapping, fishing, farming, etc., practices.

But the togetherness view can end up drawing fire. Which is good. People need to be pushed.

I suspect in the end the “Silent Sports” letter-writer would be against body-grip traps as well as the leg-hold traps he complained about. …And against hunting. And domestic livestock and pets. And eating meat. And not only for him, he’s against it for you, too. If he’s not, his more consistent friends are. The animal rights chain is all one piece. …Live by an “issue,” die by it, so to speak. You gotta follow it out.

The AR agenda would also seem to require a safety revolution in farm machinery, as well as all other machinery in contact with the earth.

But it’s understandable: No one wants living things to suffer. The mission then becomes raising your consciousness so you don’t intentionally cause needless suffering, right? …Then working to make sure your neighbor meets your personal standard. …It can get awkward.

At the same time, AR might be right. I certainly try to avoid needless killing. But what’s need? Sugar water and a cell is all I *really* need. If AR is right, what price or sacrifice is worth it to save a life? If an expensive radar attachment will prevent a tractor from crushing rodents should we still put it on all tractors? We sure spend a lot to save a human life on occasion. How does it all sort out?

Back to everyday life… Rural people would surely report someone beating, fighting, starving or unsanitary animals. They’re in favor of anti-cruelty laws. Yet they accept the captivity of farming, a dog on a chain next to a coop, fishing (but not catch’n’release, as it’s a waste of a meal!), fishing with nets or spears, hunting…and leghold trapping. How can all this be?

I note an increase in pondering questions like this. The popular Michael Pollan food-ethics books are a sign of this. The organic, locavore scene includes chickens in the yard in cities and getting in touch with the source of your meat, so that a few more cityfolk have tried hunting of late, or sympathize more with folks who live “hands on” regarding their food and the land.

Familiarity has to be an important key in all this.

Sure, we don’t need to be murderers to know it’s wrong. But sometimes experience counts.

Do people appreciate cross country skiing who’ve never done it or seen it firsthand?

Thus, are one-sided websites really the best way to judge a folkway like trapping?

When you live close to nature, among the animals… that kind of life is simply unfamiliar to those who live in town.

I ran a big trapline once upon a time. I was a woods runner, a *courier du bois*.

The short, quick truth of it is that a trapper is a farmer of the wilds. In doing it I developed a much bigger picture of the ecosystem I was in than when I hunted. Trapping also produced an enduring product of high quality. It made more sense than the “moment on the lips” empherality of a meal from hunting or fishing. So I put them on hold for those years. Trapping was the bigger game.

This brings up another angle. Even some outdoorspeople consider trappers to be scraggly lowlifes, hillbillies. There’s an elitism in the outdoor scene, to be sure. Trapping is bluecollar. Like catfishing or coon-hunting or using tracking dogs in general. These sports are often done at night after working a hard shift at a low-wage factory.

Yet some also know such sports to be the pinnacle of outdoor activity, with trapping perhaps at the top, considering the range of skills it requires, including scouting and scent, bait and gear preparation, even jiffy cabin construction. But why quibble.

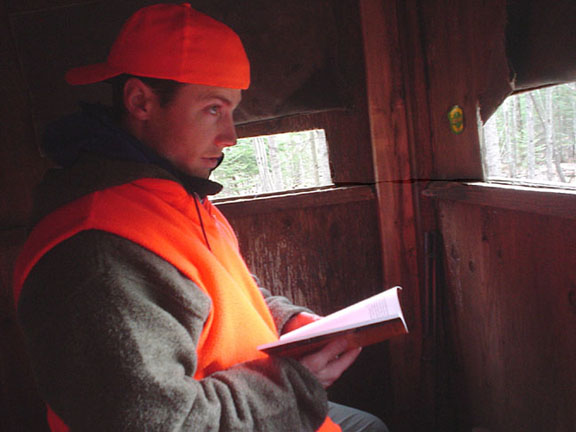

I had city friends who were put off by it. So I took them out with me. Those early morning dark-hour forays were transforming for them. They soon understood.

It’s like hunting. Considering or experiencing hunting can easily be intimidating, even if you eat meat and know a steak when you see one. When I’m away from hunting for awhile, if I’ve lived in a city awhile, even though I have a rural background, it can become disturbing to me.

Some say respecting animals means “hands off.” If so, then people must move off the land and farming likely must end as well. Yikes! This seems untenable. The likely truth is that for people to live, animals will die. Those who kill the animals to do it right need to be respectful and aware and have knowledge and connection.

Was it right for Native Americans in the past? Is it still right for them? I question whether “hands off” is indeed a higher point of consciousness. If it’s possible for a Native or some “authentic” group, it’s possible for anyone. Authenticity can be acquired.

The needed respect is all of a piece and each phase can be appreciated. So there’s killing, then there’s processing a carcass, prepping pelts, tanning furs, sewing garments, butchering meat, fileting fish. Any of the phases can be either repulsive or appealing depending on the level of understanding. When I was unfamiliar with raw meat, cutting up an animal for food was disgusting. Now a venison steak smells as good to me raw as it does cooked. Innards still can smell bad. With time and contact I suppose one would come to appreciate them as well. But these things only work when they’re part of a sustainable, responsible way of life. Yet living is growing and some may choose to leave such things behind as part of their path.

Back to the point, I’d say the suffering of an animal caught in a leg-hold trap lasts a half hour, followed by a couple hours of sleep/shock until the trapper shows up. (Most animals are caught in the early morning, when they’re most active/feeding/travelling, just before traplines are checked.) It’s no worse than if it got tangled up somehow, like in a fence. Moreover, it’s in its own environment. Harvesting wild animals offers far less interference than a domestic scenario — the only contact is at the end. Is this intolerable, unjustified, unsustainable?

I personally put wildlife harvesting ahead of farming — but then, no surprise, I’m less familiar with farming. So I won’t try to make any final judgement on them.

I also put animal killing for sport behind food or fur. But, once again, I’ve never hunted or fished just for sport, so I’ll recuse myself from judgement.

I do note that the huge hook’n’bullet sport industry is centered on money. Sure, they want to conserve the resource: for money. So they work with legislation in that direction. They may approve laws that limit leghold traps to the point where they’re ineffective for subsistence trapping and only suitable for some type of sport. With low recent fur prices, I’ve seen the rise of trapping solely for the experience of it. Something like catch’n’release fishing. But I’d rather use a gill net once a month for my food than go fish-teasing every day as a way to unwind from a stressful job of humiliating people, for instance. …Ahem.

As regards fur in general, I think people like it (in part) because it’s a sign of stewardship. It says “I know that I’m in charge and it’s life’n’death and there’s beauty for the effort.” It indicates an apex predator, but also responsibility, restraint and conservation — all present in the standard sustainable trapline scenario. One doesn’t need a “hands off” approach to the earth and the animals on it in order to be a good steward.

I understand that for some people showing your power is gauche. I know wealthy, influential folks who dress like bums. Stealth power, baby. Still, I also understand that a “captain of industry” type might want to wear fur as an apex/stewardship indicator.

Fur is renewable, in contrast to synthetics. And it’s more beautiful, more functional, less toxic, and lasts longer by far. Are synthetics ever heirlooms? (Although, I understand that in some consciousness/liberation/justice circles property and inheritance are also not in vogue. Some are even willing to kill you to liberate you from such anachronistic ideas.)

The more time I spend outside the more inclined I am toward fur. (I’m already sold on wool.) The more I learn about Native Americans and “primitive” skills (actually apex skills), the more I appreciate traditional materials in general.

I think that one of these days I’ll get a fox or muskrat fur trooper hat, or make one (or both) myself. I like the look. I’d like to catch the critters myself, or find them as roadkill. Fur prices are low so I might as well make my own garments (and maybe extras to sell) as try to sell the raw fur.

I personally really dislike seeing the carnage and waste on the roads — both human and animal — caused by careless driving. If you kill something it’s your responsibility to give it respect, to see it used for a greater good. It’s not the highway commission’s problem. A motorist should follow up and process a roadkill as much as any hunter. (If we really wanted to prevent needless suffering we’d mandate helmets and 4-point seatbelts for motorists.)

Yes, our family eats roadkill and we salvage fur from the road, too.