Here’s a tale of what happened to me and my buddies when I adopted an ocean-going sailboat moored in Lotus-land

by Jeff Potter

[I published part of this story years ago in an issue of OYB and it was reprinted in MAIB but I thought it deserved better billing than it got in my backlist of textfiles here and that it needed some color pics finally. So here goes!]

One thing led to another and I got in over my head.

There were chances of escape along the way, and at times I thought I was out, but The Boat kept coming back.

This is a huge story for me because it ties together so many of the threads of my life. It’s also really long… : ) But there are pictures! Let’s see if any of it is interesting to you.

My uncle Tim had a 30-foot wooden cruising sailboat that I first heard about when I was a teen. I was a big fan of sail adventure. The idea of Tim’s boat represented to me a Shang-Gri-La of adventure—even though I’d never seen it, nor had I ever been to L.A. where he lived and kept the boat. I knew only that an unusual relative possessed a key to freedom in an unknown, far away land.

Then, at age 22, in the mid 1980’s, some pals and I fell into the ways of hunkering and scheming. How were we to make our way boldly into the world, we wondered. I then heard the news that after my uncle moved away from L.A. that my other uncle had grown tired of paying the slip fees and that they were going to donate the boat to the Boy Scouts. It needed repair and was already arrears on rent. I approached my uncle about all this tentatively, inquiring as to his willingness to consider my pals and I as his loyal servants aboard his stately vessel, if he would but let us taste fresh sea breezes and fix the boat and pay the slip fees for him.

My uncle knew he had live ones on his hands and that, in order to set the hook properly, he’d have to stay calm. He said Maybe. Then I tried recruiting every pal I had with emergency tales of South Seas and Musketeers. No luck.

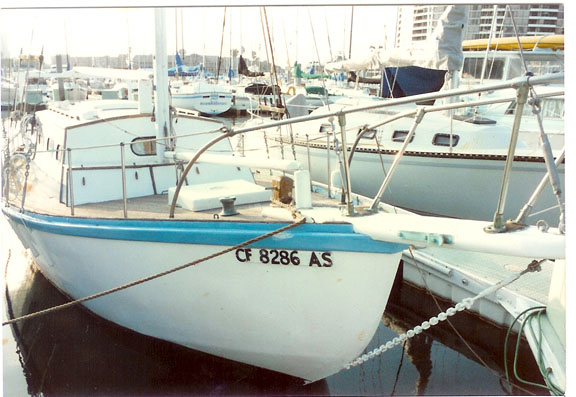

But before I quit I had to see for myself this unseen thing my heart had been pulling at me so strangely about. So I fetched my uncle in Susanville and we drove down to its home in Marina Del Rey, Los Angeles, boat-home of the stars. The day I got there I parked my Rabbit behind a Rolls on the quay. And I first laid eyes on Stampede.

It was a character boat, all right. (I just now noticed that my Rabbit is in the background of the 2nd photo.)

I was all-in. I told Unk that we should whip this pup up the coast to a more affordable hideaway. But he was unconvinced that I’d find a crew. Probably donation was the wisest path.

Since one pal was actually “on his way out” at the time, as a show of good faith I proudly popped a $1000 check on Unk. It was all I had. And a telltale sign of my desire to become involved with this boat no matter how abandoned I, too, became. For that was promptly my condition.

The money disappeared into the rent-hole faster than I wrote it out. It also gave me the deed to the boat and put responsibility for it into my lap, despite my distant residence.

So my uncles Tim and Kent and I took my new boat, Stampede, out for a day-sail. (Yes, I had paid before trying.) After a nervous and thrilling half-hour sail to the breakwater on that glorious day, I thought “Yes, indeed, sailing’s it for me!” It was my first time aboard a real boat. We rounded the breakwater. Ahh, climbing the swells, a beautiful motion. South Seas, here I come! I could hardly control myself. The whole scene seemed so right.

Ten minutes later I was puking over the side, wishing I was dead, astonished at the lack of reason for life, startled to realize the obvious mercy of God for striking people dead when he did—he did it to spare them the misery of living a second longer. “It’s OK with me if we head back in,” I said. Yes, voyaging isn’t for everyone. Life on land is a most beautiful thing…we’ll stick to land and have our fun there.

After we sailed back behind the breakwater, the sickness went away, but fatigue stayed, as did humility. I felt like I was coming out the other side of the mid-life crisis I’d always heard about. Little did I know how often I was to get this feeling in the coming few years. The uncles didn’t rub it in. They let me conclude that cutting our losses was the best thing. I presume they were nervous about it all as well. We’ll look into giving the boat to the Boy Scouts. All the long-distance hassles, all the expense…Whew! Boy, I’m lucky I wised up. What’s a thousand dollars anyway? Voyaging? –Hoo, that’s a very scary thing.

–But there was also a vibration in the air I didn’t hardly notice, one involving the uncles intentionally taking me out and getting me sick, and gladly letting me drop the monkey business and quit the quest.

They misjudged the curve. Once the bug bites you never know how far you’ll go.

But it was great hanging out in the city with the uncles and their pals. We lived it up. During the day Tim and I would be helping someone fix their car or TV or washing machine—Tim is a true genius at all that. I was his helper. Then we’d go explore a used or rare book shop. Later on a gang would form and we’d head out into the night. Someone always was flush, as they called it, and whoever was, grabbed the check. We went to Musso’s, to the great delis, to occasional fancy digs, to Phillipe’s by the tracks (the home of the French-dip), to Little Tokyo. I’d never been to a noodle bar before…especially not during lunchtime in Little Tokyo! It was like visiting a new country. We’d listen to extremely loud jazz and classical music at Kent’s house then head out to hear live jazz in town. One long evening, bracketing a jazz club, we ate dinner out twice. Those brothers were fun, I tell you. So were their friends. And I appreciated it all so much. When I first showed up in that town I was wearing my old high school clothes still. Kent said “I’ll front you an outfit if you go down right now to Melrose and buy two. And no shorts!” He had/has a voice that shook the walls. Neither of my uncles have kids and their friends’ kids were either very young or in college—I was just the right age to be able to join in with these guys at their brain-storming best.

A short time later, friends of mine came to visit. That visit lingers pleasantly with me still. …Twin blonde sisters cruised the sunny boulevards with me at the helm of a large red convertible for a couple days. Jerry, one of my uncles’ friends, noting I only had my beater Rabbit and that the visitors were energetic L.A. newcomers, loaned me this amazing car. We three went to the Improv Comedy Club where we got a warm reception.

The boat hadn’t been donated yet. So I spontaneously took the girls for a sail. Without anyone knowing. It was my only time aboard since the puke-fest. Did I remember how to operate it from watching Unk? …Have to look competent. …And don’t forget to take a Dramamine.

We had a joyous afternoon out on the bounding main. And I still can’t believe I got that 3-ton slow-turning honey out of and back into its narrow slip without destruction. I know, though, that I felt like Rocky when I gently, and completely luckily, nudged her home.

Later that week I let casually drop to the unks that I’d taken the girls out sailing. They looked at each other and raised their eyebrows. Touche’.

Then Jerry—a fun-loving businessman lawyer—said he had a vacant office building downtown that I could occupy if I wanted—so why didn’t I stick around town and work there? I was putting together a ski calendar and needed to import it from where it was being printed in Korea (an early globalizer) so I thought, Sure! What a wild offer. When the calendars came in I rented a huge truck and learned a bit about truck driving and about customs down at the big L.A. Harbor. I used boxes of calendars to create a couple desks in the empty building and brought in lawn chairs and hired an old grade school pal (who I’d bumped into!). I hooked up phones and we started cold-calling. Jerry and the uncles and I got to talking about my plans to bring friends out to adventure on the boat. They said I should do that and go a step farther and open up an afterhours club in the building, with an art gallery thrown in. What nuts! …It was enough to give a kid ideas. But what a location. The building was in Skid Row. It was the height of the homeless boom. Hundreds were living in the side streets next door. Every morning there’d be dozens of barrel fires going when I drove in at 5 a.m. to miss the traffic jam. What a world!

Three Muskateers of Marina Del Rey

The next summer I finally found pals who were willing to adventure. Praise be! All for one and one for all, Joel, Mike and I grabbed all the money we each had, loaded the faithful Rabbit, and headed to L.A. from our temporary lodgings in Breckenridge, Colorado. The fact that I was still on crutches from a broken leg didn’t seem a serious impediment—curious, in hindsight.

We arrived, paid the back rent once again, accepted the hoseannas of friends of my uncle who’d been supporting The Folly since the previous summer, and moved aboard. This was illegal, but since we were working ’round the clock to prep for a prompt departure, we got forbearance from the management.

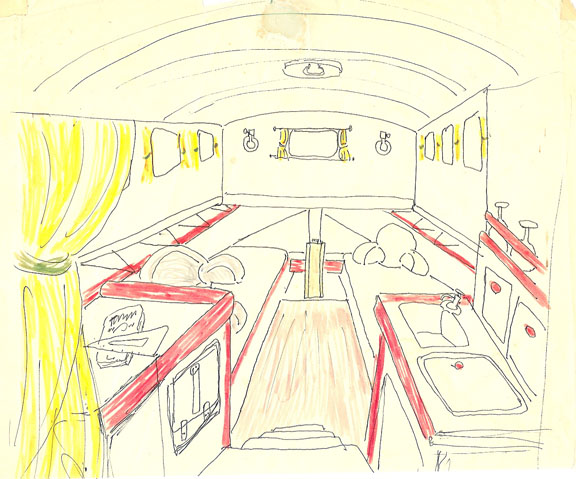

I’d never studied ole Stampede in detail the 2 other times I was on her. And I’d finally really read up on boats. Now I saw how quirky she was: a tidily homebuilt gaff-rigged cutter made of plywood on store-bought oak, with a teak deck. 26-feet on the water, 29 on the deck, with a walkable sprit. She had a huge cockpit with a solid, rather quirky banister around it, a beautiful wheel, standing headroom below, hard chines, 9-foot beam, low freeboard except for up front where her bow curved skyward, roomy foredeck and side decks. She had a modest full-length keel, and quite a cabin sticking up—she even had ratlines up the shrouds! Most of her lines were still hemp! She had a long, high boom, a modest mast. A two-by-four look to her. Yet she had salt. Damn, she did. And even though she looked a bit funny, craned their heads to see her, and they never scoffed. Fancy boat people would invite us over for drinks and comment on her looks. Our pride grew.

We coasted on our bikes through marina after marina in the huge complex, scoping the other craft for ‘reggae’ cruisiness; and we confirmed how funky we really did look. The only boat that rivaled us was an amazing old wood-and-hemp 25′ junk—both she and her young, inexperienced owner seemed to have a glint in their eyes. Our boat was clearly one of the few that looked like it might actually go somewhere. Of course, sinking outside the breakwater was also a strong part of its look.

We took Stampede out for a sail. And we became stranded as the light So-Cal breezes died on us. Then our motor developed “a problem.” We paddled with little oars, with our hands, too, as I embarrassingly recall.

We soon became the feared boat of the marina. People worried when we cast off lines even for the briefest of jaunts. People really worried when we came back—making dangerously slow turns into, first, our area’s narrow waterway, then its narrower jetty opening, then our even-narrower slip slot. Our bowsprit swung over cockpit dinner parties as pleasant people raised their arms in fear. These were our salad days. (We only had one little collision….)

Speaking of salad, after our first sail, we decided we had drag below. We spent a few days upside down underwater in the oily lagoon scraping the hull clean of hundreds of pounds of moss and shell-fish. For awhile previously we had been feeling new respect for racing sailors. What patient fellows they must be—funny how it looks like they’re going so fast, yet boats are actually so slow. At least ours was. It would hardly move. Is this sailing? We guessed so. …Then we finally cleaned our hull.

The next day-sail none of us could stop smiling. We were delighted to finally be MOVING and to hear water rushing past us rather than just a mossy forest sound. We pointed her out and refused to turn her back. We sailed out of sight of land for the first time! Freeze breezes kicked up and steadied for the first time. This was sailing! Mexico was just 100 miles south. We looked at each other. “You want to just go for it? We have everything we need!” We saw flying fish and sailed over an off-shore drop-off where the sea became indigo instead of green. The sun flashed. The spray flew.

We felt lucky to be alive. Strolling her steady teak decks made us feel like masters on a clipper ship. We also napped, as all of us gulped Dramamine whenever we left the breakwater. We sprawled against big pillows on the foredeck and in the roomy cockpit. We had a ship of plenty. And a new Bigger-Than-Life life.

At sea that day vistas opened up that we thought only existed in movies. Ships and freighters took on a sharp hugeness as we sailed close by. The smog was down. We saw mountains above and beyond L.A. The salt air was truly, idiotically, like a tonic. We looked at each other and had to slap ourselves to believe we were really doing it. Arrrr! Maties! We finally felt our priorities settling into order for once in life.

Our ship came to us with a huge stash of spare parts and gizmos. We knew nothing about them. It all looked like trash—but each gadget, we discovered in amazement, actually worked and had a definite purpose despite its homemade look. There was a self-steering apparatus made of surgical tubing, there were oldstyle lead lines (“mark twain!”), special camp-stove rigs, engine repair jigs, stuffing box stuffers—who knows what all. We also learned that the ethic of ship-shape and everything in its place is a beautiful one indeed, and we began to follow it strictly.

Over the next week, we deduced and listed what was needed in the way of repairs. Elmer’s glue and silicone seal was used a bit, but we knew there was no future in that. We tried to fix things properly.

The Atomic 4 engine fully baffled us. But she was so sweet and easy to work on that we couldn’t hold a grudge. When she ran, she gave our boat real power and had a deep, gentle pulse. It was situated out in the open in the boat, under movable stairs. And it even had a hand-crank if the starter failed. Which it did. It was unpredictable and we just couldn’t figure it out. Joel, the natural leader of our crew, repeatedly worked wonders on it while we were under way (a beer can patch he layed in saved us once) but new glitches kept springing up, giving us major headaches as we’d bob around in the luxury waterway.

Of course, we wouldn’t have needed the old beast if it weren’t for the light airs of So-Cal. (These should be abbreviated LASC.) We wanted to just blow it off, and use the ash breeze (our huge sweep oar) in the rare calms. But the calms weren’t rare. We learned that not all sailing days are spent leaned over in a strong breeze. We understood that some of the really “salty” full-bodied hulls we saw would be even worse tubs than ours until a storm came up, which is what they were designed for. Wind power is almost as bad as human power. When a boat is designed safe enough for storms then it’s too heavy and slow for typical breezes. Ugh.

By God, we swore, if our boat was somewhere where it was windy, we’d really go! Our heavy boat was brilliantly built for the sort of windy waters that obviously weren’t here. We came to appreciate the idea of mylar sails and carbon spars. We realized that one could travel quickly in a mere zephyr if your rig was light enough. But when a storm came…

This was about the time when I started to understand that having an adventure meant being surprised or having a plan go astray—both were very bad things on the ocean, or anyplace where it mattered, really. If a thing was done skillfully it went to plan and there was no adventure. So it should simply be worth doing in the first place, then you should practice it until you know what you’re doing, then do it. This takes away some of the fun but then fun is for kids—not for people in charge of large boats.

In between learning life lessons, we looked about ourselves. We rode our bikes far and wide, we visited museums and discovered the cafes and best bars of a half dozen districts. We really appreciated the art because, I think, we were trying to do something very nervy ourselves. We decided to really “step out” once and bought snappy suits from a thrift shop for an evening at the Palomino Club.

We visited old Disneyland. It was quite a trip, as they say, for us sun-burned lads. I came away with a newfound appreciation of the Pirates of the Caribbean ride. Really! …And the Peter Pan ride, too. I’d seen stars like that. And mountains in the night sky. And I’d felt the soaring elation that a boat with a steady deck…and a bone in its teeth…can give. Plus some of the piratey desperation that struggles at sea can bring on…even if they’re only with your motor.

We found the no-cover jazz clubs that blossomed in Hollywood and Burbank in that era. That creativity was inspiring. We were growing in the need to express ourselves in some way as well. We were reading each day in the paper about the writings of the Brat Pack. …We could do that. Let’s do SOMETHING!

Jerry still gave us the offer of his building for an afterhours nightclub, but we were overwhelmed as it was.

We would occasionally go visit my aunt and uncle in the Hills. They rented an apartment below their hillside house to Chuck, a syndicated showbiz columnist, a quiet bachelor of the old school who had a touch of polio. We’d hear his typewriter in the night. There was no air conditioning in the house. It was lovely, really, the way the warm night air would float through their old windows. One night the old columnist came up and we were all chatting. He caught up on the boat story. He said back 50 years ago when he was our age he and his friends did the same thing. I was surprised to hear this. Chuck used to be a pirate, too? They bought a huge leaky old schooner and moved aboard. They were cartoonists for Disney. They never sailed anywhere but they had the very best time. “Do it now, young men!” old Chucky said. What a sweet guy. He drove an ancient black Mercedes and lived simply. Couriers would come from the studios and hustle down the narrow, disheveled flowering-vine-tangled walkway to his door. (The house has AC now and Chucky is no more.)

We lounged away warm evenings in the gentle rocking of the boat, reading lights glowing, oh-so-pleasant music coming from our little Walkman with pop-on speaker. Lights reflecting across the harbor. Halyards slapping lazily all around. Car alarms going off. Happy hour feeds when we needed a change of menu. For us this was all new, and far more than we could want.

Well, there was the question of our voyage. For a month we’d been learning a lot about sailing. –Like how utterly helpless we became when the wind died and the motor failed. We finally lost Joel…to a girlfriend waiting back in the hills…and possibly to a hunch that this boat and crew weren’t safe or reliable enough or really going anywhere. Smart guy! : )

Now or Never…Into a Brave New World

The next day Mike and I realized we needed to act, engine or no engine. Our rent money ran out—and next month it was going up a huge amount. We killed both birds by waying anchor and heading south to cheaper waters with unk Tim aboard. As we took the seaward tack, Tim hunkered down to repairing the engine as only he could.

Earlier, I’d parsed out a plan at the pay-phone whereby we’d haul out to repaint the bottom in the cheapest boatyard around. The nearest ways were 50 miles to the south. We’d never sailed that far before. Now, as we rounded the big headland to reach for Long Beach, the breeze died. Tim tightened the last bolts of the refurbished carburetor and started the engine. Perfect. We motored into the evening. And arrived in a new world: L.A. Harbor.

We were big-eyed in the night as we slipped through a world of skyscraping cranes and freighters. Sounds of metal scrap sliding down troughs floated tinkling and strangely to our ears. Lights of the city on the water. Mercury lights glowing as we drift by the civilized portion–the Shops at San Pedro–a long row of restaurants, latino music, nite fishing charters backing out, full of guys, and the bright lights of a permanently moored nightclub/passenger-liner, couples dancing on the verandah, waving down at us. We chugged under high bridges, blinking in awe.

We feel like the patrol boat in Apocalypse Now. Fresh breezes ruffle our hair as we enter this dirty hard-working new world. Rugged craft jam the unkempt docks of little, squeezed-in marinas everywhere there’s not a freighter. We finally find our watery address, tie up and kick back. By God, we did it!

In the Twilight Zone on an Old Wood Boat

That 50-mile move was our longest jaunt yet. Now we were in a lunar world out of Bladerunner. Oil rigs, kleig lights, cracking stations, junkyards. Fake scenes from real movies popped up everywhere, places where we see heroes taken to be killed by drug dealers—in real life, too, we sense. The 10-mile by 10-mile harbor horizon is jam-packed with million-ton 300-foot-high bright red cranes pilfered from the Kaiser after WWI, aerial freeways over waterways, and trinket malls lining the swankier parts. All this topped with noxious fumes mixed with salt air. It was an interesting place to lay your head.

Hauled Out: Life Ten Feet Off the Ground

The next morning we have the boat hauled out and for the next nine days Mike and I work on it nonstop. We’re in the busy, rugged yard of a Portugese ship-chandler and his four sons. We work among boat-owners, old salts, bums, and many, many latino hired hands. A big family. We thought we might get out in a couple days, as every day is expensive. Wrong. We knew nothing. And we discovered that everyone you ask tells you something different when it comes to boat repair. We tried to act savvy, chewing over the diverging sage advice we were given by everyone.

Our panic on our first day hauled-out had every local declaring his own solution, in his own language. The way to success gradually dawned on us. We asked specific questions, decided for ourselves and went to it. Once we acquired the Wise Technique of the Experts we got grunted approval. Such was the Way of the Boatyard.

The boat needed hull repair and bottom painting, a rebuilt rudder, some new keel bolts and seam reglassing. No problem. Where there’s beer and sandpaper, there’s a way! (Plus money, lots of money. The local chandler is no Hope Depot, pricewise!)

As a reward, we rode our bikes after work to cheap, excellent Angeleno restaurants where we were guitar-serenaded over sun-burnt margaritas. No English speakers in sight. We felt we were accomplishing something, as every night we climbed our stepladder 9-feet up to the cockpit and fell asleep with sooty dew spotting our sleeping bags. It was so weird to wake up to the sound of jack-hammers and see you’re ten feet over a boatyard. –And a stone’s throw from a freighter and six huge cranes.

Here’s a pic from when we were up in the air:

And, God, what a bill! $900. It was all I had. We then discovered that an extremely cheap berth was opening just a hundred yards down from the boatyard. What luck! We later realized we were moving into the lives of a bunch of alky bums and their $300 floating homes, homes they gambled away with frequency.

Skid Row…Better than It Seems

What a life. But Mike and I grooved on it. We kept a decent boat bar, a sufficiency of groceries for the most part, and a daily newspaper and breakfast at a little joint at the remote end of the marina.

Our little galley felt like home. Margaritas still taste best for me in a plastic mug, with not much ice. It was truly weird to sleep so well out in that cockpit. Down below was fine, too. Those plastic bunk cushions even got to feeling good on my cheek.

Mike and I took friends out on day-sails. We had a blast. We were settling into a groove. To regain some funding, I did a stint of cold-calling to bookstores from the dock payphone.

It was at this time that I decided I wanted to publish a magazine for outdoor adventurers that told the truth. Mike and I browsed the mags and read the papers and saw the books in print: none of them expressed the reality that we saw. Among the thousand boats in the marinas around us we were among a handful who actually went sailing. The cookie-cutter clone boats—that were the subject of all the media coverage—all sat idle. The boats and the boaters who were working on them or taking them out were more like us: rich or poor, they were quirky and pushing against the grain. But they were invisible in the larger culture. I wanted to give them a voice, to let the true doers candidly share their stories and encourage—or caution—each other. But how… (The next year, 1988, I moved to Ann Arbor and bought the newly released Mac desktop publishing system to do more engineering books. It cost $14K. I also launched OYB.)

Some days after their work days, friends would come down to the boat in their suits and we’d have fresh fish waiting and we’d sail out into the evening and get the grill going. The boat was so hospitable that there might be 3 separate clusters of people chatting and drinking cocktails as the city lights faded and the night turned to stars and the water went phosphorescent in our wake. The bow area, side decks and cockpit could all hold convivial groups out for an evening’s cruise. Splendid.

Now and then Mike and I would go out for dinner, but only at Happy Hour. We found places like the crow’s nest bar of Palmer’s Lighthouse overlooking a marina in Long Beach that served all-you-can-eat fresh seafood appetizers for the price of a beer. Then there was the Barge, a floating shack that served burgers situated next to a refinery.

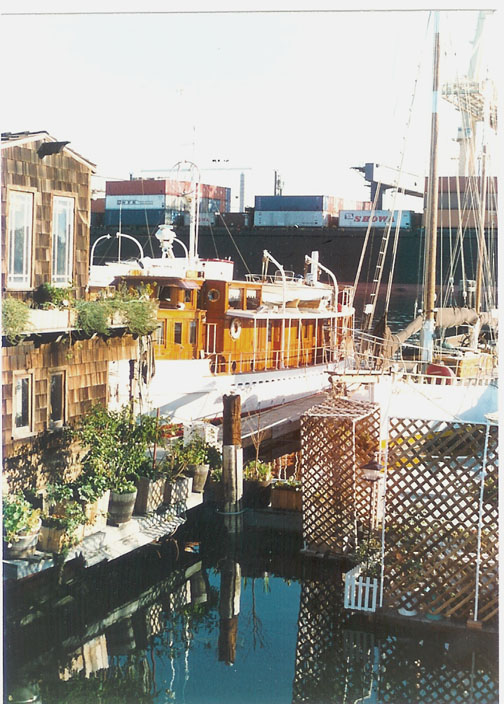

Not all our neighbors were bums. Quite a few boats were so gorgeous that even after we’d seen thousands of boats we’d say “Be still my heart.” Here’s a pic of a classic-era motor yacht next to a schooner, both docked just off a floating house. What a place to live…

Some weekends Mike would play tour guide to visiting friends and I’d take off and ride my mt-bike to visit my relatives. I would ride across town, from Long Beach, past LAX, thru cracky Compton, to Hollywood. It took me 2 hours flat—same as the bus.

Cast Off Lines! Catalina Here We Come!

After a couple weeks we were ready to make another Big Voyage. Let’s sail to Catalina Island! 28 miles! …Well, it was 34 miles from where we were moored. But we dragged our feet. There was always something more needing to be fixed.

Finally, the big day arrived—and Mike actually decided to stay ashore. For the life of me I honestly don’t know why he didn’t go—did he think we’d sink? Well…many of our neighbors told stories that would scare ya…it’s clear they enjoyed their boats just fine right there on the dock. When you got them to telling about what happened when folks strayed to the *other* side of Catalina…why…shiver me timbers! Believe me, we had a sense of the “all or nothing” nature of big boats and big oceans. One bump could sink ya or cost ya big-time…and we had no reserves. Mike was a funny, witty guy…and maybe actually sensible in the end.

So I embarked with a neighbor, John, a pudgy, loud guy who volunteered when I announced the “It’s Time To Go!” alarm. He brought aboard three cases of Burgie Beer for the jaunt. I was nervous, both about the vast amount of beer and about the neighbor. The rule of the area was “friends to everyone, but trust no one.” Too many cops beating on boat decks with billy clubs, too many calls to the dock phone from guys needing to be bailed out from jail.

But it was now or never. …We cast off and soon were sailing faster than ever, with stout breezes all the way to Catalina—averaging 5 knots! We finally sailed somewhere exotic. And I finally got to steer into an unknown, crowded anchorage at night! Avalon Harbor…yes! We even took a water taxi ashore!

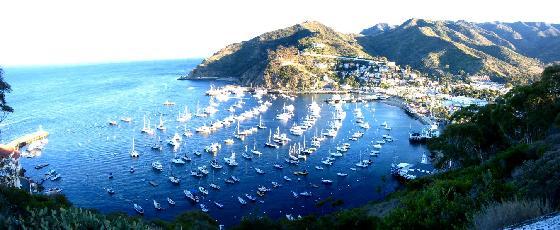

Here are a couple stock photos of Avalon Harbor nabbed from the google:

You have to understand that we’d listen on our little radio to a cosmic jazz station at night, in our cockpit campout, amid the sounds of the harbor and the salt air. It was the first time we heard the song “Avalon” by Roxy Music. It swept us away. …And now here I had navigated us, at night, to Avalon Harbor. I was pleased.

What Neighbors are Made of

My boat-neighbor pal, John, even with fifteen beers in him, proved a boon companion–if a little too boon. He was rolly-poly and had a huge mane of curly hair and handlebar mustache. He padded about the boat with bear-like bare feet, admiring it. He saw its rugged capability. Why, if it weren’t for his whatever-it-was, his troubles, he would be sailing for the South Seas right now in his own boat…

After a night of debauch, bankrupcy, and John arguing with strangers about billiards, bets and dames, I went back to the boat. John returned at 4 a.m….by way of swimming…since he wanted to stay out and had no taxi money. I was asleep in the cockpit when he heaved in like a seal up over the rail, shaking wet, totally drunk, booming “Christ! My cigarettes are wet!”

We were faced the next morning with no food (great planning, huh?!) and with the question of getting to shore, a quarter mile away. We were penniless (more good planning!). And we were without a dinghy. (Don’t all voyages begin with someone saying, “Aw, heck, let’s go!”) Obviously, John said–with me scarcely believing he was still alive–we get all our spare lines, tie them together, then tie the end to this surf-board he brought along. One guy paddles ashore, the guy on the boat pulls the surfboard the quarter-mile back then he paddles ashore. It worked of course.

Actually, I had $1.15 which I had kept from the demands of alcohol the night before and declared my low intention of getting a meager breakfast, though that meant that John would go without. Not nice, but look at him, he wasn’t nice, either. “Meager breakfast, my ass,” said John and off he went. I sat down for a tiny plate of hash-browns. Ten minutes later John returns, “Here’s money, now let’s go get steak and eggs!” He’d pestered bartenders ’til he found one who’d give him a loan and came back to me–who’d abandoned him–and bought us a huge round of chow.

John had brought fins over to the island–he gave me one and we hopped into the harbor water. I saw many things new to me under there. Brilliant turquoise vistas flowing away across the entire harbor. Flights of red, orange, green fish. –How much more could one newcomer to oceans take?! I noticed an old bent-up one-speed bike on the bottom. Then I saw John motioning that I help him recover it. A true-blue scavenger!

After a bit of shore rest, I returned to the water, gingerly crabbing my way through the rocks of the surf. I said “C’mon, John, creep through this way, it’s easy.” He stood up, all blubber, on a big rock near shore, staring into the surf. “Naw,” he said, looking into the surf, “that’s too easy.” Timing himself with the arrival of a wave, he—“Wait,” I blurted, “you can’t do”—dove into what used to be six inches of water over sharp rocks, with a belly-flop most useful, and came frog-kicking out to me. It was the most stylin’ move I’d ever seen.

We then had another great sail back to the harbor where I regaled Mike with the weekend’s tales.

Our first real voyage had turned out magnificently, 3 cases of Burgie Beer and no money notwithstanding.

But back to style and nobility—the people of the ocean have a special spark, I found time and again. Back when the boat was on the ways, we had encountered an elderly widow lady in jeans who had a couple of kids our age with her. She asked what we were up to and immediately I knew something was special about her. All weathered and grey, she still had a twinkle in her eye. But her kids whined, and their boat was primitive and dumpy. Later, she told me her story. She and her husband sailed in that same boat to New Zealand in the 1950’s. She and he dove and salvaged to earn their way. And she gave birth to her son on that boat. He was raised in the South Pacific, but when they had a daughter they finally sailed back for home in the USA. The boat caught fire in the middle of the ocean and they began to row away from it in their dinghy–man, wife and two kids. And then it rained, and their boat was saved. Now she was getting its bottom painted. That’s the kind of “something extra” I mean.

Here’s a pic of that Tahiti boat and the boy who was born on it:

Another time I met a big, young underwater salvage guy at a bar after work. He made $250/hour to take a power-hose underwater and blast it down under the seabed so he could wrap a huge chain around some sunken structure. But it was he himself who’d have to crawl down under the seabed with the chain and hose—and the muck would collapse in behind him as he went until he blasted his way back up and out again and could tie off the chain. He was happy to be alive—some of his pals weren’t. He had a girl on his arm who he didn’t seem to know, and bought rounds on the house. I then finally understood why some people bust up bars for fun and get tattoos and earrings. Here was a guy who could stand and yell “Arrr, Matey!” whenever he wanted.

Coming and Going, Mountain and Sea

It was the mid-80’s now. Work was pressing from my real job. The little engineering book project that I started with my dad (who was an engineering professor) was selling more and taking more time to shepherd. Soon I had to leave L.A. to return to Colorado where my “real” home now was. Mike, too. But the boat was safe and snug, all fixed up, in a cheap slip. I’d have to groom ski trails and sell books to pay for it until I could find a new adventure pal somehow.

I returned that winter once again for a book trade show. What a funny thing it is to lead a dual life. I’d be staying on the musty little boat, then emerge each morning in coat and tie to the hung-over teasings of my dock neighbors, and hike out through the refineries to catch a bus into Long Beach. I tell ya, it’s the best thing to fly out of a Colorado winter and wake up with a palm tree overhead, flowers on the jetty, halyards slapping and the sounds of wind, water and boat-traffic on the breeze! That refinery oil and that tinkling scrap really did get to sound sweet to me!

I kept planning to motor the boat through the waterways to the convention center as it was next to the water. I could entertain clients on it. What a gas! But the engine started acting up again. Argh.

I tell ya, the neatest thing about having a boat is taking it to public moorings outside a popular bistro. What a way to arrive! …Cars aren’t the only way to go, people!

John was still living on his boat down the dock a ways. But he’d laid off the Burgie Beer. His hair was shorter. He still had wild ideas. I saw him rowing past the marina one day in a tiny dinghy, towing a huge log—“Salvage!” he yelled. He came to me one day. He knew this old lady who owned an oil well down the street. We could set up the rig and be in action…whattaya say? Whoa… Sadly, I cannot now say that I ever worked on an oil rig.

That first year I picked up uncle Tim way up in Susanville (near Reno) to come down and scope out the boat, it took quite awhile to get him moving. There were nightly 500 games with his cronies, one of whom was a rancher. (500 is po’ man’s bridge.) So it turns out that I *did* get to work a real round-up, with real cowboys, who actually came riding in off the range on horses, wearing yellow slickers. That was *the most intense* work day of my life.

Anyway, after saying no to oil I left to groom ski trails then returned to L.A. the next summer for yet another convention. This time I stayed to finish off The Boat. It was exciting to be a broke wing-nut in the mountains with an ocean cruising yacht in L.A. The idea is charming. But the reality was too much. No real partner was on the horizon—how can you find a seafarer in the Rocky Mountains? (I found one but he turned out to be a drug-dealer. He was a great guy but our worlds did not converge well enough.) The slip fees suddenly doubled. It was time to sell.

I’d learned a few things along the way. A big lesson was that if you wanted to sail, go look for any of a million boat-owners who need help sailing and go sail with them. If you want the peculiar feel of ownership, buy a boat—you might not ever sail, though.

Another lesson: Asking price means nothing with boats. Timing is everything. Depending on the ever-evolving desperation of an owner, any size and type of boat can be purchased for as little as $1000, say. Step two: However much money you possess, it will be spent on that boat. You will be broke. But in your mind, it’ll be for a bold and mighty cause.

It’s hilarious to hear crazy boat talk from otherwise intelligent people. A physician once told me enthusiastically of a 70-foot motor-sailer that he could buy for a mere $12,000! Lord, I thought, people really do fall down these holes, don’t they. I asked my pal if he had $20,000 spare change yearly from now until eternity. I also predicted, with a tired, sage tone, that that vessel could be had, at some point within three months, for $1000. But he’d still need to supply the yearly treasure chest. Oh.

So I ran want-ads. And went close to broke from ad fees. –That’s how the boat life works. Any one factor can almost do you in, now add up a dozen of them.

I nearly went bonkers from the want-ad goose chases. I learned to ferret out sincerity–no, that wouldn’t narrow it down enough–I looked for intention to buy now, and spiked the rest. Sorry, bye.

I’d been making little sailing forays in the meantime. I invited pals and newly-met acquaintances aboard for evening cocktail cruises. Let me tell you, not too many members of my bottom caste can do this. We did. We barbequed giant shrimps that neighbors dropped off whole, in buckets. Quiet reggae or jazz mixing nicely with wine in thrift shop wine glasses as we idled along. Strolling the deck. –God, you could stroll my deck. I’d leave the big carved wheel, engine rumbling away, and stroll on forward with other folks and stand and chat and scarcely hear the engine. So we’d glide through the skyscraper-high bridge-bright lights-lonely nights. Heaven.

Other times I’d go out sailing alone in the day–even if the engine wasn’t working. I’d just give it a shove then line the backward-drifting boat through my neighbor’s sterns, then quietly kick off and hop onto the bow pulpit and let a breeze catch me as I hoisted the sail. Not too many other people did that. I guess they were sensible. But I’d head out to sea and meet the spanking breezes and feel like I could go on forever. I might cross paths with another single-hander, him aboard his $100,000 yacht, share nods of equality. Usually no other boat would be out. I’d set a course, the boat flying on a reach, heeling solidly. God, it was like a house afloat. I’d go below and cook up soup and tea, just to do it, and look out my window and notice a leaning, shimmering lighthouse. Hot damn, this is sure different from normal!

Here’s a pic, taken while heading out on one such solo outing…

Then I’d head back in, maybe glide on in effortlessly on a zephyr, maybe get becalmed and the engine wouldn’t start so I’d scull in with my huge sweep oar, maybe get a tow, maybe almost get run over.

It was silly trying to be a ski racer in the mountains and own a boat in L.A. at the same time. But also: what a rare opportunity! So I’d try to stay in shape while living on the boat. There was about a mile of road between the freeway and the refinery that I could run on. I’d do push-ups and pull-ups down at the dock. Sell books from the payphone. It was hilarious.

In the days of waiting I even started working for Lupe, the marina manager. I’d ride around the harbor with him on his Mule barge, picking up project boats. I’d drive with him to his nearby bario to pick up workers. I tried learning some Spanish but they had no idea I wasn’t just saying something kooky in English. Man, I loved that local ceviche for lunch!

Here’s Lupe doing his thing with a nice boat:

I kept taking little cocktail parties out for night-time cruises. Out past the glow of all city lights. Phosphorescence lit everything underwater with that unbelievable Peter Pan glow. Nobody ever believed me when I told them it would happen. I loved taking them out to where they could see the sea’s own light. All teasing and snickering would cease in stunned awe. On these jaunts we sometimes got scares from coming too close to huge buoys we missed seeing from behind the sail, or come too close to big ships, or get wildly rocked by big bow waves. One guy nearly fell from wildly swaying spreaders once; he hung dangling in his coat and tie; I’d forgotten he was up there in the ratlines while making sure we were safely passed by a trawler. It was a world full of overwhelming things.

I even made the hilarious discovery, by accident, that Walter, one of the friends who had been caretaking the boat for my uncle before I took it over, was the boyfriend of the mom of Flea, the bassist for the Red Hot Chili Peppers…and that the whole band used to go out sailing on my boat! The friend was a jazz bass player and I had been going to hear him at Simply Blues (30 floors up at the corner of Sunset and Vine, baby!) whenever I was in town. The kicker is that he invited me to a big backyard 4th of July party at his girlfriend’s house—her kids were in a band and they and their friends would be there. That’s all I heard. I decided I wanted a quiet holiday and passed it up. The next week I went out for dinner with them (at a great gardeny seafood place halfway up Topanga Canyon called “Seventh Ray”—it looks fancier now from their website) and that’s when I figured it out that the band was the Peppers and the friends were stars and models. Doh!

But no one was buying and I was getting weary. The asking price of my boat bottomed out. Not $1000 anymore: $500 takes all.

During the next couple weeks, however, the boat worked its perverse magic on me all over again. I had more cozy “house-at-sea” sails. The price climbed back with my morale. A new-found mechanic friend and I finally fixed the engine for good. It was a simple, tiny short. (All that pain!) Hey, she was almost good as new now…maybe I should keep her! The mechanic kept coming back for more sails as I took prospective customers out for evening jaunts.

I rode a 3-speed bike I borrowed from my aunt the 5 miles to Dominguez Hills bicycle velodrome and joined in on race workouts.

In the next week I met more wondrous sailors. Savvy, wacky Viet vets and friendly, potential boat buyers. Everything on the boat started working perfectly. Everyone who came in contact with her was charmed, enchanted.

I finally landed a winner at $5000. In a neighborhood of knife-fights and boozy thefts, I demanded risky cash rather than a dubious check and unhesitatingly asked to follow my puzzled suburban buyer to his bank. The big roll felt good.

It was time to head home. The elemental life was getting to me. Like driving a motorcycle across the country without a helmet or windshield, then finding out you have to turn around and drive back. –Too much fresh air. On the way to the airport, I forgot to drop off at the boat the two outboard motors that were stashed at my uncle’s. Then I lost my ticket. Somehow I lost a ticket right on the carpet, in the aisle, after the metal detector. My lip starts to quiver. Shouting gets me nowhere with the attendants—and my plane leaves with my luggage. The next cheap flight away from the land of palm trees is at 5 a.m. Arrgh! Next flight possible: Ten minutes. …For three times as much. I pull out the roll, peel off the bills. And run. Arrive in Denver. No chance to alert a friend as to the flight change, so she’d just left. It’s midnight and I do catch the last bus to Boulder. Carry my heavy duffle up the hill. There’s a light dusting of snow. Crisp, clean air. I’m starting to feel better already. The mountains—that was home, too. But tired. How tired can a person get?

It was a good long ride, though. The five grand was gone by the next day after I paid the bills and sent half to old uncle Tim as a token tip.

And I was missing ole Stampede already.

I still do.